Galician language

| Galician | ||

|---|---|---|

| Galego | ||

| Pronunciation | [ɡaˈleɡo] | |

| Spoken in | ||

| Total speakers | 3–4 million (500,000 emigrants throughout Ibero-America and Europe) | |

| Language family | Indo-European | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in | Galicia, Spain; accepted orally as Portuguese by the European Union Parliament. | |

| Regulated by | Real Academia Galega | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1 | gl | |

| ISO 639-2 | glg | |

| ISO 639-3 | glg | |

| Linguasphere | ||

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Galician (Galego) is a language of the Western Ibero-Romance branch, spoken in Galicia, an autonomous community located in northwestern Spain, as well as in border zones of the neighbouring territories of Asturias, Castile and León and northern Portugal.

Modern Galician and modern Portuguese are descended from a single Latin derived language which linguists today call Galician-Portuguese or Mediaeval Galician or Old Portuguese. This common ancesteral language was spoken in the territories of the mediaeval Kingdom of Galicia.

Contents |

Classification

Historically, the Galician-Portuguese language originated in the lands now in Galicia, Asturias and northern Portugal, which belonged to the mediaeval Kingdom of Galicia, itself comprising the former Roman territory of Gallaecia. The language diverged into two in the 14th century after the County of Portugal became an independent state and the Portuguese reconquista imposed its own version of the language on its conquests to the south. There are linguists who consider modern Galician and modern Portuguese as dialects or varieties of the same language, but this is a matter of debate. For instance, in past editions of the Encyclopædia Britannica, Galician was called a Portuguese dialect spoken in northwestern Spain. However, the Galician community does not regard Galician as a variety of Portuguese but as a distinct language. They point out that modern Galician descended, without interruption and in situ, from mediaeval Galician. Mutual intelligibility (estimated at 85% by Robert A. Hall, Jr., 1989[1]) is good between Galicians and Portuguese speakers from Portugal's northern provinces of Alto-Minho and Trás-os-Montes but noticeably poorer between Galicians and speakers from central and southern Portugal.

Relation to Portuguese

The linguistic status of Galician with respect to Portuguese is controversial as the issue sometimes carries political overtones. Some authors, such as Lindley Cintra,[2] consider that they are still dialects of a common language, in spite of superficial differences in phonology and vocabulary. Others, such as Pilar Vázquez Cuesta,[3] argue that they have become separate languages due to major differences in phonetics and vocabulary usage, and, to a lesser extent, morphology and syntax. The official position of the Galician Language Institute is that Galician and Portuguese should be considered independent languages. The standard orthography is noticeably different from the Portuguese partly because of the divergent phonological features and partly due to the use of Spanish (Castilian) orthographic conventions.

The relationship involving Galician and Portuguese can be compared with that between Macedonian and Bulgarian, Aromanian with Romanian, Occitan and Catalan, or English and Lowland Scots: language proximity conflicts with political interpretation.

The official institution regulating the Galician language, backed by Galician government and universities, is Real Academia Galega, claims that modern Galician must be considered an independent Romance language that belongs to the group of Ibero-Romance languages and has strong ties with Portuguese and its northern dialects.

There is also a minority, unofficial institution, Associaçom Galega da Língua (AGAL, Galician Association of the Language), belonging to the Reintegrationist movement, according to which differences between Galician and Portuguese speech are not enough to consider them separate languages, and Galician is simply one variety of Galician-Portuguese, along with Brazilian Portuguese; African Portuguese; the Galician-Portuguese still spoken in Spanish Extremadura, Fala; and other dialects.

Geographic distribution

Galician is spoken by more than three million people, including most of the population of Galicia, as well as among many people of Galician origin elsewhere in Spain (Madrid, Barcelona, Biscay), and Galician immigrants to other European countries Europe (Andorra, Geneva, London and Paris), and Ibero-America (Buenos Aires, Montevideo, Havana, Caracas, Mexico City, São Paulo, Guadalajara, Veracruz City and Panama City).

Controversy exists regarding the inclusion of Eonavian dialects spoken in westernmost Asturias into the Galician language, with those defending Eonavian as a dialect of transition to the Astur-Leonese group on the one hand, and those defending it as clearly Galician on the other.

Because of its historical status as a non-official language, for some authors the situation of language domination in Galicia could be called "diglossia," with Galician in the lower part of the dialect continuum, and Spanish at the top; while for others, the conditions for diglossia established by Ferguson are not met.

Currently, the most common language for everyday use in the largest cities of Galicia is Castilian (Spanish) rather than Galician, as a result of a long process of language shift. Galician is still the main language in the rural areas, though.

Official status

Spain has recognized Galician as one of Spain's five "official languages" (lenguas españolas), the others being Castilian (also called Spanish), Catalan (or Valencian), Basque and Aranese. Galician is taught bilingually alongside Castilian in both primary and secondary education, and is used as the primary medium of education at universities in Galicia. Further, it has been accepted orally as Portuguese in the European Parliament[4] and used as such by, among others, the Galician representatives José Posada, Camilo Nogueira and Xosé Manuel Beiras.

Dialects

Galician has three principal dialects, each of them divided in local areas of mutual intelligibility.

- Eastern Galician

Divided in four areas: Asturian area (Eonavian), Ancares area, Zamora area and Central Western area.

- Central Galician:

Divided in four areas; Mindoniensis area, Lucu-auriensis area, Central transitional area and Eastern transitional area.

- Western Galician:

Divided in four areas; Bergantiños area, Finisterre area, Pontevedra area and Lower Limia area.

Examples

| I Western | II Central | III Eastern | Portuguese | Spanish | English |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pantalóns | Pantalós | Pantalois | Calças | Pantalones | Pantaloons/Trousers |

| Cans | Cas | Cais | Cães | Canes/Perros | Canines/Dogs |

| Avións | Aviós | Aviois | Aviões | Aviones | Airplanes |

History

| Excerpt of medieval Galician poetry, with English translation |

|---|

| Porque no mundo mengou a verdade, |

| punhei un día de a ir buscar; |

| e, u por ela fui a preguntar, |

| disseron todos: «Alhur la buscade, |

| ca de tal guisa se foi a perder, |

| que non podemos én novas haver |

| nen ja non anda na irmaidade». |

| ~o~o~o~ |

| Because in the world the truth has faded, |

| I decided to go and search for it |

| and wherever I asked |

| everybody said: 'search in another place |

| because truth is lost in such a way |

| such as we can have no news of it |

| and it's no longer around here' |

| Joan Airas (13th century) |

From the 8th century, Galicia was a political unit within the kingdoms of Asturias and León, but was able to reach a degree of autonomy, becoming an independent kingdom at certain times in the tenth, eleventh and twelfth centuries. Galician was the only language in spoken use, and Latin was used, to a decreasing extent, as a written language. This monopoly on spoken language was able to exert such pressure in the 13th century, that it led to a situation of dual official status for Galician and Latin in notarial documents, edicts, lawsuits, etc.; Latin, however, continued to be the universal vehicle for higher culture.

Written texts in Galician have only been found dating from the end of the 12th century, because Latin continued to be the cultured language (not only in Galicia, but also throughout medieval Europe).

The oldest known document is the poem Ora faz ost'o Senhor de Navarra by Joam Soares de Paiva, written around 1200. The first non-literary documents in Galician-Portuguese date from the early 13th century, the Noticia de Torto (1211) and the Testamento of Afonso II of Portugal (1214), both samples of medieval notarial prose.

In the Middle Ages, Galaico-português (or Galician-Portuguese) was a language of culture, poetry, and religion throughout not only Galicia and Portugal, but also Castile (where Castilian was used mainly for prose).

After the separation of Portuguese and Galician, Galician was considered provincial, and it was not widely used for literary or academic purposes until its renaissance in the mid-19th century.

With the advent of democracy, Galician has been brought into the country's institutions, and it is now co-official with Spanish in Galicia. Galician is taught in schools, and there is a public Galician-language television channel, TVG.

The Real Academia Galega and other Galician institutions celebrate each May 17 as "Día das Letras Galegas" ("Galician Literature Day"), dedicated each year to a deceased Galician-language writer chosen by the academy.

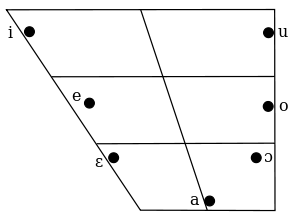

Phonology

| Phoneme (IPA) | Grapheme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| /a/ | a | nada |

| /e/ | e | tres |

| /ɛ/ | e | ferro |

| /i/ | i | min |

| /o/ | o | bonito |

| /ɔ/ | o | home |

| /u/ | u | rúa |

| Phoneme (IPA) | Grapheme | Example |

|---|---|---|

| /b/ | b/v | banco, vaca |

| /θ/ | z/c | cero, zume |

| /tʃ/ | ch | chama |

| /d/ | d | dixo |

| /f/ | f | falo |

| /ɡ/ or /ħ/ | g/gu | galego, guerra |

| /k/ | c/qu | conta, quente |

| /l/ | l | luns |

| /ʝ/ or /ʎ/ | ll | botella |

| /m/ | m | mellor |

| /n/ | n | nove |

| /ɲ/ | ñ | mañá |

| /ŋ/ | nh | algunha |

| /p/ | p | por |

| /ɾ/ | r | hora |

| /r/ | r/rr | recto, ferro |

| /s/ | s | sal |

| /t/ | t | tinto |

| /ʃ/ | x | viaxe |

See also Wikipedia in Galician: Official orthography of Galician.

Almost all dialects of Galician have lost nasal vowels. However, vowels can become nasalized in proximity to nasal consonants. Along the modern age, Galician consonants went through significant changes which closely paralleled the evolution of the Spanish consonants, namely the following sound changes, eliminating voiced fricative consonants:

- /β/ → /b/;

- /z/ → /s/;

- /dz/ → /ts/ → /s/ in western dialects or /θ/ in eastern and central dialects;

- /ʒ/ → /ʃ/;

For a comparison, see Differences between Spanish and Portuguese: Sibilants. Additionally, during the 17th and 18th centuries the western and central dialects of Galician developed a voiceless fricative pronunciation of /ɡ/ (a phenomenon called gheada). This may be glottal [h], pharyngeal [ħ], uvular [χ], or velar [x].[5]

Spanish has been experiencing a centuries-long consonant shift in which the lateral consonant /ʎ/ comes to be pronounced as a fricative /ʝ/ (see yeísmo). This merger, which is almost complete for Spanish in Spain, has somewhat influenced other linguistic varieties spoken in Spain, including some Galician ones, but it is rejected by Galician language institutions.

In this respect, it can be said that Portuguese is phonologically more conservative than Galician.

Grammar

Galician allows pronominal clitics to be attached to indicative and subjunctive forms, as does Portuguese, unlike modern Spanish. After many centuries of close contact between the two languages, Galician has also adopted many loan words from Spanish, and some calques of Spanish syntax.

Writing system

The current official Galician orthography was introduced in 1982, and made law in 1983, by the Real Academia Galega (RAG), based on a report by the ILG. It remains a source of contention, however; a minority of citizens would rather have the institutions recognize Galician as a Portuguese variety as cited before, and therefore still opt for the use of writing systems that range from adapted medieval Galician-Portuguese writing system or European Portuguese one (see reintegrationism).

In July 2003 the Real Academia Galega (Galician Royal Academy) modified the language normative to admit some archaic Galician-Portuguese forms conserved in modern Portuguese. These changes have been considered an attempt to build a consensus among major Galician philology trends and represent, in the words of the Galician Language Academy, "the orthography desired by 95% of Galician people." The 2003 reform is thought to put an end to the so-called "normative wars" raised by the different points of view of the relationship between the modern Galician and Portuguese languages. This modification has been accepted only by a part of the reintegrationist movement at this point.

The question of the spelling system has very significant political connotations in Galicia. At present there are minor but significant political parties representing points of view that range from greater self-government for Galicia within the Spanish political setup to total political independence from Spain designed to preserve the Galician culture and language from the risk of being inundated by the Castilian culture and language. Since the modern Galician orthography is somewhat influenced by Castilian spelling conventions, some parties wish to remove it. Since medieval Galician and medieval Portuguese were the same language, modern Portuguese spelling is nearer to medieval Galician than to modern Galician Spanish-style spelling. Language unification would also have the benefit of linking the Galician language to another major language with its own extensive cultural production, which would weaken the links that bind Galicia and Spain and ultimately favor the people's aspiration toward an independent state. However, although all three concepts are frequently associated, there is no direct interrelation between reintegrationism, independentism and defending Galician and Portuguese linguistic unity, and, in fact, reintegrationism is only a small force within the Galician nationalist movement.

Examples

| English | Galician (Official) | Galician (Reintegrationist) | Portuguese | Spanish |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Good morning | Bo día / Bos días | Bom Dia | Bom Dia / Bons dias | Buenos días |

| What is your name? | Como te chamas? | ¿Cómo te llamas? | ||

| I love you | Quérote / Ámote | Amo-te | Te quiero / Te amo | |

| Excuse me | Desculpe | Perdón / Disculpe | ||

| Thanks / Thank you | Grazas | Obrigado | Gracias | |

| Welcome | Benvido | Bem-vido | Bem-vindo | Bienvenido |

| Goodbye | Adeus* | Adiós | ||

| Yes | Si | Sim | Sí | |

| No | Non | Nom | Não | No |

| Dog | Can | Cam | Cão | Perro (Rarely Can)[6] |

| Grandfather | Avó /aˈbo/ | Avô** /ɐˈvo/ | Abuelo | |

| Newspaper | Periódico / Xornal | Jornal | Periódico | |

| Mirror | Espello | Espelho | Espejo | |

*In Galician and Brazilian Portuguese, adeus is rarely used (signifies that one will not see that person for many years or anymore, comparable to the use of English "farewell"). Ata logo is more common and literally means "until later" (Portuguese até logo, Spanish hasta luego).

**Note that avó /ɐˈvɔ/ in Portuguese means "grandmother".

| Galician official | Galician reintegrationist | Portuguese | Spanish | Latin |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Noso Pai que estás no ceo: | Nosso Pai que estás no Céu: | Pai Nosso que estais no Céu: | Padre nuestro que estás en los cielos: | Pater noster qui es in celis: |

| santificado sexa o teu nome, veña a nós o teu reino e fágase a túa vontade aquí na terra coma no ceo. | santificado seja o Teu nome, venha a nós o Teu reino e seja feita a Tua vontade aqui na terra como nos Céus. | santificado seja o Vosso nome, venha a nós o Vosso reino, seja feita a Vossa vontade assim na Terra como no Céu. | santificado sea tu Nombre, venga a nosotros tu reino y hágase tu voluntad en la tierra como en el cielo. | sanctificetur nomen tuum, adveniat regnum tuum et fiat voluntas tua sicut in terra et in celo. |

| O noso pan de cada día dánolo hoxe; | O nosso pam de cada dia dá-no-lo hoje; | O pão nosso de cada dia nos dai hoje; | Danos hoy nuestro pan de cada día; | panem nostrum quotidiamum da nobis hodie; |

| e perdóanos as nosas ofensas como tamén perdoamos nós a quen nos ten ofendido; | e perdoa-nos as nossas ofensas como também perdoamos nós a quem nos tem ofendido; | Perdoai-nos as nossas ofensas assim como nós perdoamos a quem nos tem ofendido; | y perdona nuestras ofensas como también nosotros perdonamos a los que nos ofenden; | et dimite nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimitimus debitoribus nostris; |

| e non nos deixes caer na tentación, mais líbranos do mal. | e nom nos deixes cair na tentaçom, mas livra-nos do mal. | e não nos deixeis cair em tentação, mas livrai-nos do mal. | no nos dejes caer en tentación, y líbranos del mal. | et ne nos inducas in temptationem; sed libera nos a malo |

| Amen. | Amen. | Amen. | Amen. | Amen. |

See also

- Barallete

- Castrapo

- Eonavian

- Fala dos arxinas, a jargon of Galician masons

- Fala language

- Galician literature

- Galician-Portuguese

- Leonese language

- Portuguese language

Notes

- ↑ Ethnologue

- ↑ Lindley Cintra, Luís F. Nova Proposta de Classificação dos Dialectos Galego-PortuguesesPDF (469 KiB) Boletim de Filologia, Lisboa, Centro de Estudos Filológicos, 1971. (Portuguese)

- ↑ Vázquez Cuesta, Pilar «Non son reintegracionista», interview given to La Voz de Galicia on 22/02/2002 (in Galician).

- ↑ EUobserver

- ↑ Regueira (1996:120)

- ↑ Real Academia Española

Bibliography

- Regueira, Xose (1996), "Galician", Journal of the International Phonetic Association 26 (2): 119–122

External links

- Appendix:Galician pronouns - on Wiktionary

- LOIA: Open guide to Galician Language (English).

Newspapers in Galician:

- Luns a Venres - free daily newspaper (in official Galician)

- Galiciaé.es - online news portal (in official Galician)

- Galicia Hoxe - daily newspaper (in official Galician)

- A Nosa Terra - weekly newspaper (in official Galician)

- Vieiros - online news portal (in official Galician)

- Gznacion - online news portal (in official Galician)

- Arroutada Noticias - online news portal (in official Galician)

- Novas da Galiza - monthly newspaper (in reintegrationist Galician)

- Galiza Livre - pro-independence online news portal (in reintegrationist Galician)

Other links related to Galician:

- Real Academia Galega (official Galician)

- Instituto da Lingua Galega (official Galician)

- A Mesa pola Normalización Lingüística (official Galician)

- Associaçom Galega da Língua - Portal Galego da Língua (reintegrationist Galician)

- Movimento Defesa da Lingua (reintegrationist Galician)

- Biblioteca Virtual Galega (official Galician)

- Sound recordings of the different dialects of the Galician language (official Galician)

- Ethnologue report for Galician (English)

- English-Galician CLUVI Online Dictionary (official Galician), (English))

- Basic information on Galician language (official Galician), (Spanish), (English)

- Galician - English Dictionary: from Webster's Online Dictionary - The Rosetta Edition. (Official Galician), (English)

- A short English-Galician-Japanese Phraselist (Renewal) incl. sound soft (Official Galician), (English), (Japanese)

- Amostra comparativa - Comparison between Galician, Portuguese and Brazilian-Portuguese pronunciation (with sound files) (reintegrationist Galician)

- Flocos.tv: Films in Galician language (official Galician)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||